Never individuals, though.

Over the years, though, I’ve had the opportunity to fly solo on several software projects, some short lived, some longer, as have other ALM consultants that I know. One thing we all seem to have in common is that, while as ALM experts, we have all of the skills and knowhow to apply our own trade to the software we develop, we seldom – if ever – do so.

The Cobbler’s Children Go Barefoot…

… as the saying goes. It seems that this proverb applies to our profession as much as it does to others. You’ve seen the doctor who smokes, the out-of-shape coach, the technician or plumber whose own wiring or plumbing is faulty, respectively. Perhaps it’s the same. Perhaps its just that proper ALM is more visibly useful when multiple hands are involved and they must all communicate and interact properly with each other, than when one person holds all roles.

… as the saying goes. It seems that this proverb applies to our profession as much as it does to others. You’ve seen the doctor who smokes, the out-of-shape coach, the technician or plumber whose own wiring or plumbing is faulty, respectively. Perhaps it’s the same. Perhaps its just that proper ALM is more visibly useful when multiple hands are involved and they must all communicate and interact properly with each other, than when one person holds all roles.

Solo projects seem to need no management, I believe they only seem to.

Here’s why:

1. If You Don’t Use Source Code Version Control, You’re an Idiot!

I guess I couldn’t rephrase it without the vehemence. Lesson learned.

Beyond the fact that having some kind of backup, preferably online, means that even if you lose your laptop, or accidentally delete your source files, you still have a copy of your code, version control means that if you make a mistake, you can still rollback to that point in time and fix whatever you did wrong. Having a historical log of the changes you made to the software can also serve as release notes of sort, and a rudimentary list of the features and bug fixes you have, and even help establish some kind of time line.

Really though, version control is about security for the code – protection against loss and against mistakes. you should use it as frequently as possible.

Note that you do not need to shell out huge amounts of money to be able to use version control. In fact, as in life, so with version management, the best things are free!

I prefer using Git. You can use it locally with any operating system (Windows, Linux, Mac OS), and there are multiple online tools that work and synchronize with Git, all free: GitHub, CodePlex, and (my personal favorite) Visual Studio Online. There are, of course, other version control systems, both distributed and centralized (Mercurial is another DVCS, Subversion is a great free centralized one).

Heck, even use DropBox or some other online-syncing file-storage, just beware that it won’t protect you from deleting your code, nor will it let you rollback – but at least you’

2. Defining (just enough) Work Upfront = Less Code Writing and Rewriting

And let’s be clear. Just enough is key here. Too little, and you’ll rewrite anything that you haven’t properly thought out and planned. Too much, of course, and changes to the reality surrounding the project and your perception of reality will bring rewrite to your plans.

3. Project Planning Makes it Possible to Plan Releases

- When will it be done?

- What will be done by a certain date?

Without estimating the work you have to do, more so if you don’t even know how much work you have, you simply will not be able to give more than a POOMA estimate.

Note that unless you live alone, you might still need to answer these questions, if only so your partner, roommate or parent will know when you will finally clear the garage (or dinner table) from your junk.

4. Automation Reduces Human Error as well as Manual Labor

- You’re only human.

- You’re only one human.

Being only human means that as talented as you may be, you are still prone to repetition based errors. You’ll forget to update the version number, or forget to set the build configuration to Release, or forget to run the tests, or any number of things. When I train new developers, especially in those early days when they feel that the fact that they’re constantly making errors, and more experienced developers must be demigods or some such, in an attempt to reassure them (and lighten the atmosphere), I tell them this:

- There are only two kinds of developers: experienced, and inexperienced developers.

- Inexperienced developers make only two kinds of mistakes: Mistakes born of inexperience, and mistakes born of stupidity.

- Experienced developers make mistakes only born of stupidity

Aside from the fact that this is inherently true (an experienced person, by definition, cannot make a mistake born of inexperience), it is important to note – experienced developers make mistakes!

Computers do not. Ever.

Another saying that I’m fond of repeating, the former statement being a key reason to do so, especially when consulting and or training clients on the use of ALM tools, is to never let a human do a machine’s work (and vice versa). Anything a machine can do, we shouldn’t.

Another saying that I’m fond of repeating, the former statement being a key reason to do so, especially when consulting and or training clients on the use of ALM tools, is to never let a human do a machine’s work (and vice versa). Anything a machine can do, we shouldn’t.

Finally, there’s the fact that any time spent on doing what someone, or more importantly, something (i.e. your computer) could do, is time not spent on things only you can do (i.e. developing the product – which you’d probably prefer to do anyway). Ask yourself this – while you’re manually doing repetitive work – who is coding? Nobody.

This holds true for building, for testing, for releasing and deploying, and basically for anything that you can (and know how to) automate.

In all but the simplest and most straightforward scenarios (usually short-term, one-shot projects), you should find ways to delegate work to a machine.

5. Defining the Work Makes Change Management Easier

It’s all great when you’re hacking away at that pet-project of yours and you’re in the zone, but a week later, a month or even three later, once you start delivering a second or third release of your software, keeping track of what was done, when – not to mention writing release notes, becomes extremely difficult, if you don’t know what your changes are or were. In fact, if you use an ALM tool for tracking features, changes and defects, and associate them with automated builds, you can generate a release notes document automatically with every build, and not have to deal with it yourself.

It’s all great when you’re hacking away at that pet-project of yours and you’re in the zone, but a week later, a month or even three later, once you start delivering a second or third release of your software, keeping track of what was done, when – not to mention writing release notes, becomes extremely difficult, if you don’t know what your changes are or were. In fact, if you use an ALM tool for tracking features, changes and defects, and associate them with automated builds, you can generate a release notes document automatically with every build, and not have to deal with it yourself.

The other kind of change, is change of management. Today this may be your solo project. Tomorrow, who knows? You may take on a partner, give someone else the code to maintain, or decide to open the source. If the only definition of the work is whatever lies inside that wonderful brain of yours, hand-off will be a bear. Trust me. I’ve had to waste two weeks once receiving a project, and I still don’t know everything about it. Finding out stuff on my own is not the best use of my time. Having a nice set of features, tasks and bugs (past and open both) shortens the time, and makes discovery pains all but gone.

Conclusion

In summary, I’d like to state my opinion that in most (again, all but the simplest and most straightforward one-shot) software projects, proper ALM is as useful and important when flying solo as when developing with a team. Lack of communication issues (though see point #5) are balanced by the increase of work of having to do it all by yourself.

In summary, I’d like to state my opinion that in most (again, all but the simplest and most straightforward one-shot) software projects, proper ALM is as useful and important when flying solo as when developing with a team. Lack of communication issues (though see point #5) are balanced by the increase of work of having to do it all by yourself.

Just do it right the first time. You’ll thank me for it.

Best Regards,

Assaf Stone

Occasional Solo Developer

This post is a bit different than my usual ones. Instead of orating off of my soapbox, I’d like to share a moment of agile bliss that I had today. One of the teams I work with at my customer’s company conducted their first “truly agile” sprint planning session. This post is a recount of the experience.

This post is a bit different than my usual ones. Instead of orating off of my soapbox, I’d like to share a moment of agile bliss that I had today. One of the teams I work with at my customer’s company conducted their first “truly agile” sprint planning session. This post is a recount of the experience.

At the end of the meeting, the team leader expressed his regrets that we don’t have a full-time technical-product-manager (TPM) which is the closest role they have to a Product Owner. The group manager, who was present for the Sprint Planning picked up the impediment and answered “Let’s take it offline; I’ll try to get one to join the team ASAP”.

At the end of the meeting, the team leader expressed his regrets that we don’t have a full-time technical-product-manager (TPM) which is the closest role they have to a Product Owner. The group manager, who was present for the Sprint Planning picked up the impediment and answered “Let’s take it offline; I’ll try to get one to join the team ASAP”.  INVEST is a another great acronym from the Computer Sciences industry, Department of Agile (yes, DOA, and I’m well aware – thank you very much); It stands for Independent, Negotiable, Valuable, Estimable, Sized (or Small), and Testable. Those are indeed valuable attributes of User Stories, of any kind of requirements at all, and the acronym itself implies some effort on behalf of the creator of user stories (i.e. the Product Owner), with a potential return on investment.

INVEST is a another great acronym from the Computer Sciences industry, Department of Agile (yes, DOA, and I’m well aware – thank you very much); It stands for Independent, Negotiable, Valuable, Estimable, Sized (or Small), and Testable. Those are indeed valuable attributes of User Stories, of any kind of requirements at all, and the acronym itself implies some effort on behalf of the creator of user stories (i.e. the Product Owner), with a potential return on investment.

You’d think that given the high premium on the time of developers, and the fact that most projects are running late, as it is, it would go without saying that everything we develop is valuable. Unfortunately that is not the case. According to the CHAOS Report, by the

You’d think that given the high premium on the time of developers, and the fact that most projects are running late, as it is, it would go without saying that everything we develop is valuable. Unfortunately that is not the case. According to the CHAOS Report, by the

At the end of the day (or at least, at the end of the planning session), any estimation is just a guess: sometimes its more, and sometimes its less. This means that the distribution of the actual time versus the estimation should be pretty much

At the end of the day (or at least, at the end of the planning session), any estimation is just a guess: sometimes its more, and sometimes its less. This means that the distribution of the actual time versus the estimation should be pretty much  The better the estimation technique is, the steeper the curve will be, i.e. the closer actual results will be to the estimation.

The better the estimation technique is, the steeper the curve will be, i.e. the closer actual results will be to the estimation.

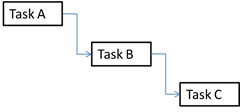

It is easy to see that the more complex a project is, the more dependencies each task has the greater the chance of being late is; The distribution of the actual duration of tasks with dependencies is a

It is easy to see that the more complex a project is, the more dependencies each task has the greater the chance of being late is; The distribution of the actual duration of tasks with dependencies is a