Today I read an

article on TechRepublic about how robots and computers automate more and more roles previously carried out by humans, and how we won’t like what’s left.

We all know what’s coming, manual labor will be replaced by machines, leaving only the jobs that (still) require a human mind. I’m sure you cannot throw a stone without hitting a politician or spokesperson who will tell you that this is bad, but at the risk of coming off as a detached and condescending elitist, I will have to respectfully disagree.

Change Happens

Change happens. Always. This isn’t a new thing. Change has been happening since the beginning of time. Literally. Without change we’d still be a potentially explosive situation in the middle of nothing, because the Big Bang wouldn’t have happened.

Okay. I’ll agree that that was just some demagoguery. Forget everything that happened in the last couple of billions of years. Let’s limit the discussion to technological advances. Disruptive ones. Like agriculture. Advances were being made that changed the world, and the roles humans played in it. It started some 10,000 years ago, and is still going on today. Still not convinced? Still think this is demagoguery? Okay, I’ll put that aside too. Let’s talk “real” technological changes.

How about the Industrial Revolution? Those factories? Them machines sure replaced a lot of people didn’t they? Please note that that was going on some 250 years ago.

Change is a Good Thing

The Japanese word “Kaizen” literally translates to “Good Change”. Now, I’ll say straight up that not all change is good, hence the differentiation, but I believe that it is more often better than it is worse. I don’t have any scientific proof of it, but I seriously doubt that anyone could argue that their lot in life is actually worse than it would be if they were in their comparable station in life in or around 18th century Earth. I think that even people living in 3rd world countries all over the globe are as well of as they’d be, or better. I believe that just being able to discuss their issue, having first world people become aware of 3rd world people is an improvement. We, as a rule are becoming better people.

Please note, that the comparison I am making is between one person, and his or her own lot in a world “stuck” in the past. I believe that inequality, while it is a touchy subject, is irrelevant here. I know that there are people who hunger for bread living a few miles from people who have more money than they could ever spend. But was that not always the case? I believe that I myself, my friends, and probably anyone who has a computer, tablet or smartphone with which to read this post lives better than most nobles did a few centuries ago, and better than any king just a few centuries before that. And I’m just making a (fairly) decent living.

So What is the Problem?

Adapting to change is difficult. Disruptive change, more so. When something that you know, and believe in may become invalidated and obsolete, it may feel overwhelming and scary. Other times it just makes you feel irrelevant – just like your (now useless) knowledge.

People have been losing their jobs to machines since forever, possibly since ten thousand years ago, definitely in the past 250 years. But this isn’t a bad thing!

For every manual laborer whose skills were no longer necessary, two jobs showed up for factory line workers. Old jobs transformed to adapt to the new world. New jobs were created. Some people adapted, others did not. Those of us who adapted were better off for it. Those who didn’t, weren’t. And we can and should feel sorry for them, and that is okay, and it is okay to rejoice in our own improved lot, because the change made our lives better, as a rule, or it wouldn’t have happened.

The issue at hand, I believe is that change itself has changed!

Change is Changing!

Change was always happening, and the rate of change was always increasing. But where in the past change happened over billions of years, until it could be measured in millions of years, and human advancement was then measured in millennia, at some point changes became so great and so quick that we started to notice. The industrial revolution was, I believe, the first such point in time, with change so great and so fast that it one could perceive life before and after it, within one’s own lifetime. Since then the changes began to happen every several decades – factories, the telegraph, automobiles, airplanes, radio, television, computers…

Computers.

From the 1943 legendary statement, (allegedly) made by

Thomas J Watson that “there is a world market for maybe five computers”, to a national average (US) of

more than five (5.7) internet connected devices per household(!). In 70 years, computers have transformed (almost) everything that we do, allowing us to do more, much more, in less – much less – time. Everything. Including research work. This means that the

rate of change itself has changed, dramatically and visibly increasing.

Why, up until roughly 20 years ago, hardly anybody outside colleges had any personal or commercial access to this overgrown, BBS-on-steroids thing called the internet. Ten years ago, I had a palm pilot, had a slow GPRS modem to connect to it, and was the only one I knew that had one such. Seven years ago, the first iPhone came out, and while there were “smart” phones before, it was the first device that was actually accessible for the general population.

Now?

More than half of the entire world population have mobile phones. 31.1% of the population have internet access, meaning that

just under a third of the people in the world have access to the sum total knowledge of human knowledge(!). Let’s ignore the fact that most people’s usage has nothing to do with knowledge (except in the biblical sense).

The Pros

Is this a good thing? I think it is. For me personally, at least. I cannot imagine being able to do my work, without access to millions of code samples, documentation, tools, guides, online books, etc. Twenty years ago I had to remember most of the software languages that I use, or else take a (heavy) book off the shelf and flip through what I couldn’t remember. Ten years ago I had intellisense and computers had enough memory and disk space for references to be stored on disk for quick access. Today I don’t ever bother to install the help, documentation and SDKs that come with the tools and languages that I use. It is quicker to Google it. Googling even became a word. Almost everybody knows it and does it (except for those who must

Baidu it, and those who choose to Bing it, and those elitists who prefer to duck-duck-go it).

The Cons

Some people take exception at this change. From developers who claim that Microsoft-stack coders who rely on

intellisense have become crippled by their inability to code without it, to my wife who gets upset because I do not (cannot?) remember anything that isn’t on my calendar, people believe that we who rely on the internet to remember for us have lost something by giving up the skill of memorization.

Personally, I think that a skill that is no longer needed is not worth having except for recreational purposes. I don’t remember how to sheer sheep, gut a fish or skin a rabbit, because I never knew how to do these things. I never needed to learn (though if I did, I’m sure I could

Google it).

My main argument is that it is foolish to waste brain power in learning things that will soon become obsolete.

And that is our problem

Changing is Difficult. Not Changing is Fatal

Saw this quote somewhere. It is largely true, I believe. For myself, I love change. I can’t wait to see what the next big thing is, what’s over the horizon? What new technology will come out tomorrow…While I appreciate my own generation’s unique stand point, being born on the cutting edge, riding the wave of technological change, We are immigrants to this brave new world. I would love to have been born today, to be a true child of the millennium, to be born a native child of the world of technology. What does my eldest daughter at 13 feel, never knowing a world without the internet? How will my baby experience the world, growing up in a world where scientific and technological advances I can barely imaging will be common place?

But it is a constant struggle, riding the wave. One must adapt to change quickly, one must learn to devalue what one knows, in favor of what can understand and extrapolate. Hanging on to yesterday will cause you to fall into the chasm with it.

I figured that out on my own. My children will have that engrained in them. But many of my generation don’t understand that. Most of my father’s generation do not. How surprised are we to see our parents have a truly thriving online presence? Our grandparents? I learned to work with computers at an extremely young age, because I saw my father, one of very few at the time, using one, programming. My kids still perceive me as an expert on technology, though I already defer to my daughter in some areas (social networks, mostly).

My mom can operate a computer if told exactly what to do, step by step. I have friends whose mothers can read their email, because they have to, as part of their work, but go to pieces if things don’t work just right, because they fear the computer. Computers are alien to them, and the change they bring is beyond them.

My grandmother, and some uncles will still want to explain to me how to get somewhere, all while I politely explain that I just need the name of a place or an address and Google Maps will do for the rest.

That’s all okay, they have their ways of doing things, and I have my

waze.

But not at the workplace.

At the office, at the factory, time is money, and anything that a computer can do, it can do faster and with greater precision than any human can cope to do.

And once a computer can do something, it is only a short matter of time before it will replace a human doing it.

What will such human do?

Learn to do something new, or become extinct, obsolete, unemployed.

The Way of Tomorrow Today

At any job interview, I will tell my would be employer that the biggest asset that I bring is adaptability, my ability to learn, knowing how to know. More than one customer asked me a question, and when he saw me searching the internet for the answer, he or she asked me something to the equivalent of “If you don’t know the answer why am I paying you”? My answer is always a simple statement that I’m paid because I know enough about my domain to Google faster than anyone he or she employs, I know where to search, I can understand what I read faster, and extrapolate a better solution to the problem than anyone else (perhaps a bit arrogant, but selling yourself short is never a good idea, and stammering any other answer would be worse).

What is my point? My point is this, in order to thrive in the world today, one must cultivate the skill of learning in one’s domain of expertise. One must learn to adapt to disruptive change, to seek out these changes and prepare, to look for opportunities to adapt first and come out on top.

That, or fade away. Or hope you can retire before becoming completely obsolete.

I consider myself lucky (though I believe in making my own luck), I could never as a kid sit down in one place at school and learn to retain knowledge I considered useless. I instead learned quickly on my feet, figuring things out in the middle of a test, extrapolating from whatever I learned before. Today this a prized skill.

Others who are less lucky have to learn now. Change will never stop. Not everybody will hold back, and not everybody will stop inventing new ways to replace human labor with computers. Perhaps one day it will all be computers and machines doing the work, and perhaps we can become a utopian society where machines can sustain comfortable human life for all, and people will simply do what ever they can to make themselves and the world better, not for monetary reward, but because they want to fulfill themselves (see – this isn’t communism).

One can hope.

And adapt.

Adapting to change is difficult. Disruptive change, more so. When something that you know, and believe in may become invalidated and obsolete, it may feel overwhelming and scary. Other times it just makes you feel irrelevant – just like your (now useless) knowledge.

Adapting to change is difficult. Disruptive change, more so. When something that you know, and believe in may become invalidated and obsolete, it may feel overwhelming and scary. Other times it just makes you feel irrelevant – just like your (now useless) knowledge. Change was always happening, and the rate of change was always increasing. But where in the past change happened over billions of years, until it could be measured in millions of years, and human advancement was then measured in millennia, at some point changes became so great and so quick that we started to notice. The industrial revolution was, I believe, the first such point in time, with change so great and so fast that it one could perceive life before and after it, within one’s own lifetime. Since then the changes began to happen every several decades – factories, the telegraph, automobiles, airplanes, radio, television, computers…

Change was always happening, and the rate of change was always increasing. But where in the past change happened over billions of years, until it could be measured in millions of years, and human advancement was then measured in millennia, at some point changes became so great and so quick that we started to notice. The industrial revolution was, I believe, the first such point in time, with change so great and so fast that it one could perceive life before and after it, within one’s own lifetime. Since then the changes began to happen every several decades – factories, the telegraph, automobiles, airplanes, radio, television, computers… Saw this quote somewhere. It is largely true, I believe. For myself, I love change. I can’t wait to see what the next big thing is, what’s over the horizon? What new technology will come out tomorrow…While I appreciate my own generation’s unique stand point, being born on the cutting edge, riding the wave of technological change, We are immigrants to this brave new world. I would love to have been born today, to be a true child of the millennium, to be born a native child of the world of technology. What does my eldest daughter at 13 feel, never knowing a world without the internet? How will my baby experience the world, growing up in a world where scientific and technological advances I can barely imaging will be common place?

Saw this quote somewhere. It is largely true, I believe. For myself, I love change. I can’t wait to see what the next big thing is, what’s over the horizon? What new technology will come out tomorrow…While I appreciate my own generation’s unique stand point, being born on the cutting edge, riding the wave of technological change, We are immigrants to this brave new world. I would love to have been born today, to be a true child of the millennium, to be born a native child of the world of technology. What does my eldest daughter at 13 feel, never knowing a world without the internet? How will my baby experience the world, growing up in a world where scientific and technological advances I can barely imaging will be common place? At any job interview, I will tell my would be employer that the biggest asset that I bring is adaptability, my ability to learn, knowing how to know. More than one customer asked me a question, and when he saw me searching the internet for the answer, he or she asked me something to the equivalent of “If you don’t know the answer why am I paying you”? My answer is always a simple statement that I’m paid because I know enough about my domain to Google faster than anyone he or she employs, I know where to search, I can understand what I read faster, and extrapolate a better solution to the problem than anyone else (perhaps a bit arrogant, but selling yourself short is never a good idea, and stammering any other answer would be worse).

At any job interview, I will tell my would be employer that the biggest asset that I bring is adaptability, my ability to learn, knowing how to know. More than one customer asked me a question, and when he saw me searching the internet for the answer, he or she asked me something to the equivalent of “If you don’t know the answer why am I paying you”? My answer is always a simple statement that I’m paid because I know enough about my domain to Google faster than anyone he or she employs, I know where to search, I can understand what I read faster, and extrapolate a better solution to the problem than anyone else (perhaps a bit arrogant, but selling yourself short is never a good idea, and stammering any other answer would be worse).

An on-call technical support engineer wakes up groggily at 2am, when his phone rings. It’s a department manager. “Huhhhh? Huhhlllo?” he mumbles into the phone.

An on-call technical support engineer wakes up groggily at 2am, when his phone rings. It’s a department manager. “Huhhhh? Huhhlllo?” he mumbles into the phone. No, I’m not the new number two. I’m just another developer, who has to solve problems with software, and consequentially, solve problems in the software that solves the problems. I get bug reports coming from end users, testers, middle managers – sometimes even fellow developers – that leave me without anything more than a general sense that there was a disturbance in the force, and the software is not performing within acceptable parameters.

No, I’m not the new number two. I’m just another developer, who has to solve problems with software, and consequentially, solve problems in the software that solves the problems. I get bug reports coming from end users, testers, middle managers – sometimes even fellow developers – that leave me without anything more than a general sense that there was a disturbance in the force, and the software is not performing within acceptable parameters.  Jokes aside, we usually do not insert bugs into the system intentionally. At best it was the one defect that slipped the developers’ scrutiny. Often it is the product of being rushed to meet a tight deadline. At worst it is the result of negligent work born of the despair of either not knowing how to work properly and worse – knowing how things should be done, but not being able to do them the right way (see aforementioned deadline).

Jokes aside, we usually do not insert bugs into the system intentionally. At best it was the one defect that slipped the developers’ scrutiny. Often it is the product of being rushed to meet a tight deadline. At worst it is the result of negligent work born of the despair of either not knowing how to work properly and worse – knowing how things should be done, but not being able to do them the right way (see aforementioned deadline).

Yes, for god’s sake, we believe you. We don’t think that you’re off your rocker, if you have one. We need whatever evidence you have to help us identify the problem, find its source, and resolve it. So if you have it, give it up:

Yes, for god’s sake, we believe you. We don’t think that you’re off your rocker, if you have one. We need whatever evidence you have to help us identify the problem, find its source, and resolve it. So if you have it, give it up: Especially if you are a developer or tester, you might have a special configuration file with specific setting that you are using. Please provide any non-sensitive configuration, or at least describe it. Anything you know about how you use the software can shorten the time it takes to fix the problem.

Especially if you are a developer or tester, you might have a special configuration file with specific setting that you are using. Please provide any non-sensitive configuration, or at least describe it. Anything you know about how you use the software can shorten the time it takes to fix the problem. No, it’s not a cynical way of stating that that’s the way the cookie crumbles. We don’t always know what you believe the normal behavior should be. You may be right, you may be wrong. If you’re right, we need to fix it. If you’re wrong (i.e. the infamous “not a bug”, a.k.a. “by design” / “as designed”), we need to fix our documentation. So please let us know what you expect.

No, it’s not a cynical way of stating that that’s the way the cookie crumbles. We don’t always know what you believe the normal behavior should be. You may be right, you may be wrong. If you’re right, we need to fix it. If you’re wrong (i.e. the infamous “not a bug”, a.k.a. “by design” / “as designed”), we need to fix our documentation. So please let us know what you expect.

Okay, this one goes out to all you developers out there. There is nothing our coworkers hate hearing from us more than this line. It is not okay. It is still your responsibility to resolve the problem. I once worked with a manager that suggested that any developer that shrugs a defect off with “it works fine on my machine”, will be shipped off to the customer with his machine, in order to solve the problem. Said customer was in another country, where summer temperatures reached over 50 degrees Celsius (122°F!). To my knowledge the threat was never actually carried out, but the developers there used the phrase less than any other team I’ve worked with.

Okay, this one goes out to all you developers out there. There is nothing our coworkers hate hearing from us more than this line. It is not okay. It is still your responsibility to resolve the problem. I once worked with a manager that suggested that any developer that shrugs a defect off with “it works fine on my machine”, will be shipped off to the customer with his machine, in order to solve the problem. Said customer was in another country, where summer temperatures reached over 50 degrees Celsius (122°F!). To my knowledge the threat was never actually carried out, but the developers there used the phrase less than any other team I’ve worked with. Sometimes a bug will consistently appear whenever the application is executed. In other cases it might be limited to happening only sporadically:

Sometimes a bug will consistently appear whenever the application is executed. In other cases it might be limited to happening only sporadically: This one goes especially for corporate and enterprise users, as well as testers in teams. Nobody expects Joe Six-Pack to go knocking on doors in order to figure out if he’s special or part of something bigger.

This one goes especially for corporate and enterprise users, as well as testers in teams. Nobody expects Joe Six-Pack to go knocking on doors in order to figure out if he’s special or part of something bigger.

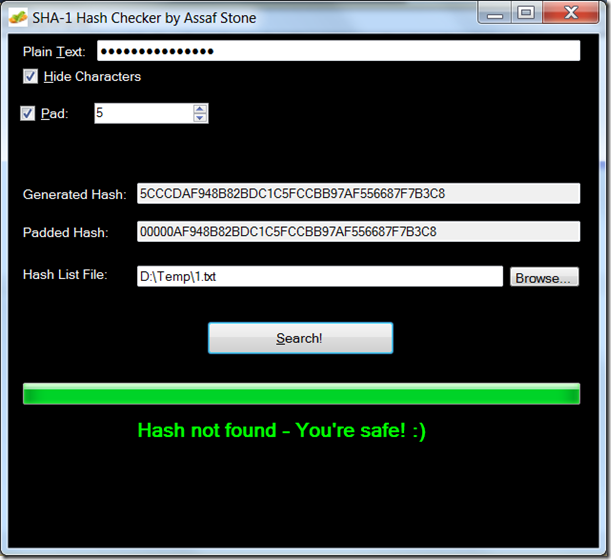

The most naïve (and dangerous – never do it like that) solution is to store the password in plain-text, i.e. unencrypted. What these sites do, when you log in, is send the user-name and password (often unencrypted) over the internet, to the site, and then compare the given password with the stored one. If they’re the same, the user authenticated.

The most naïve (and dangerous – never do it like that) solution is to store the password in plain-text, i.e. unencrypted. What these sites do, when you log in, is send the user-name and password (often unencrypted) over the internet, to the site, and then compare the given password with the stored one. If they’re the same, the user authenticated.

This post is a bit different than my usual ones. Instead of orating off of my soapbox, I’d like to share a moment of agile bliss that I had today. One of the teams I work with at my customer’s company conducted their first “truly agile” sprint planning session. This post is a recount of the experience.

This post is a bit different than my usual ones. Instead of orating off of my soapbox, I’d like to share a moment of agile bliss that I had today. One of the teams I work with at my customer’s company conducted their first “truly agile” sprint planning session. This post is a recount of the experience.

At the end of the meeting, the team leader expressed his regrets that we don’t have a full-time technical-product-manager (TPM) which is the closest role they have to a Product Owner. The group manager, who was present for the Sprint Planning picked up the impediment and answered “Let’s take it offline; I’ll try to get one to join the team ASAP”.

At the end of the meeting, the team leader expressed his regrets that we don’t have a full-time technical-product-manager (TPM) which is the closest role they have to a Product Owner. The group manager, who was present for the Sprint Planning picked up the impediment and answered “Let’s take it offline; I’ll try to get one to join the team ASAP”.