INVEST is a another great acronym from the Computer Sciences industry, Department of Agile (yes, DOA, and I’m well aware – thank you very much); It stands for Independent, Negotiable, Valuable, Estimable, Sized (or Small), and Testable. Those are indeed valuable attributes of User Stories, of any kind of requirements at all, and the acronym itself implies some effort on behalf of the creator of user stories (i.e. the Product Owner), with a potential return on investment.

INVEST is a another great acronym from the Computer Sciences industry, Department of Agile (yes, DOA, and I’m well aware – thank you very much); It stands for Independent, Negotiable, Valuable, Estimable, Sized (or Small), and Testable. Those are indeed valuable attributes of User Stories, of any kind of requirements at all, and the acronym itself implies some effort on behalf of the creator of user stories (i.e. the Product Owner), with a potential return on investment.

But that isn’t good enough. A catchy name may be enough for most developers to try something new (seriously, when does a developer ever need a reason to try something new?), but not so for management. To many managers, however, this can sound like Impossible, Not-gonna-deliver, Vague, Everything-is, So-what, and Test-the-whole-goddamn-project!

In this post, inspired by a twitter-conversation I had a while ago, I hope to explain what this INVESTing in user stories really means, and why it is worth doing.

I is for INDEPENDENT

Of course, most of the work in writing good user stories is in this part as well. You are required to reimagine how you think of your work. You need to do away with layered one-shot thinking that is probably necessary in every industry except software. Since the actual construction of the software is for all intents and purposes near-instantaneous, you can (and should) think about vertical increments of value, when you come up with your requirements. Each such story should be worded so as to be independent of any previous (or forthcoming) stories.

In some cases, you may find it impossible to break a story’s dependencies, no matter how you try. In those cases, try to look at the story with its dependencies as a single story. Find the commonality of them and reimagine it.

To summarize – Independence in your stories will translate directly into increased probability of delivering on time!

N is for NEGOTIABLE

The full meaning of negotiability, is that the contents of the story (i.e. scope, priority, requirements) can be changed at any time, from the moment they are introduced, and up until the the developers commit to it (i.e. the beginning of its sprint).

This is perhaps both the easiest attribute to add to your user stories, and the hardest. It is easy, because it requires no extra work from the PO or team. It is hard, because it may require you to let go of any preconceptions you may have of the story (i.e. those you had when you first wrote it). It requires you to allow people to move your cheese.

The return on this investment is quite valuable, however; Your stories will be rejuvenated, and will be more valuable to the customers and user, because they have been recently revalued, evaluated and updated. This attribute is particularly synergetic with the next one:

V is for VALUABLE

You’d think that given the high premium on the time of developers, and the fact that most projects are running late, as it is, it would go without saying that everything we develop is valuable. Unfortunately that is not the case. According to the CHAOS Report, by the Standish Group, fully 64% of developed functionality is rarely or never used!

You’d think that given the high premium on the time of developers, and the fact that most projects are running late, as it is, it would go without saying that everything we develop is valuable. Unfortunately that is not the case. According to the CHAOS Report, by the Standish Group, fully 64% of developed functionality is rarely or never used!

All of these features have something in common: They were added without any consideration of their value or necessity to the users or the customers!

The valuable attribute of user stories helps reduce these numbers, by making sure that anything and everything the team develops has value to the users. When the PO comes up with a story, and cannot find a way to describe its value, it is possible that there is no value. Our tendency to add these valueless stories to the product comes from the traditional idea that you have to define everything upfront, or it won’t be in the project. Thanks to negotiability, it is possible to focus only on what is valuable.

This attribute also protects the system from developers’ desires to build a framework (we all love developing frameworks – it’s a conditioning or something), or do any work that doesn’t translate into value to the customer. If some technical work is required for some story, add the work as a task to that story, not as a technical story; this will more clearly radiate to management what is required to complete a story, and will give the PO the ability to consider this extra work and its impact when evaluating the story.

E is for ESTIMABLE

There is more to it, though, than just the techniques. The story should be clearly scoped. There should be a beginning and an end.

Imagine a story such as “As a user, I want a text editor, so that I can take notes”. How much will it take to develop that? I have no idea. If the user only needs a multi-line textbox with persistence capabilities, then I can probably have it done in a few hours (yes – a few hours, because nothing ever takes just 5 minutes!). If the user is expecting RTF capabilities with copy and paste, it’ll take longer, and if he’s looking to give MS Word some serious competition, it’ll probably take a few man-years (just guessing here; It’s too big for me to give a good estimate).

I see estimability as the culmination and grounding of the next two attributes, Size and Testability (see below).

S is for Size

This attribute requires the PO to define in detail what it is that he wants the team to deliver. In many cases, the actual user stories that the team works on are the elaboration of the broad scopes defined in the “Epics” or “over-stories” or “super-stories”.

What the PO gains is the ability to release early and often. The team get the ability to create less complex solutions, because the problems are smaller.

Remember, the story should be defined in terms of their business value, not the implementation details! The details are to be left to the developer tasks, and are of no interest to the users or customers.

T is for Testable

This last, but most certainly not least of attributes serves everybody who has a stake in the product:

- By defining the story’s acceptance criteria, the PO has the opportunity to define more specific demands of the story, than what appear simply in the “title” (“As a… I want… so that…).

- Both the Developers and the QA gain an understanding of what the scope of the story is and what it is not, thus reducing a great source of contention about whether something is a bug, or a new feature (if I had a penny…)

- Stakeholders gain an understanding of what they are going to receive by the release.

The acceptance criteria, like the rest of the story, should be worded in the product’s domain language, which means that they should be defined in the users’ terms, rather than the developer / QA terms.

The return on your INVESTment here should be obvious: The PO gains a tighter control of what will be produced, without unnecessarily elaborating on the technical solution, while the developers and QA have a better understanding of what they are required to do.

In conclusion

I think that every part of the INVEST model has value. Stories that you have invested in will be:

- More likely to complete on time

- Current and updated

- Valuable to the customer and / or the users, with less unnecessary technical fluff

- Clearer, with less dissonance between POs, developers and testers

- Less complex to develop, easier to test, and quicker to get feedback as well as quicker to deploy

- Easier to prove and validate and quicker to gain acceptance by the customer / user

That’s all. I think it’s a worthy goal, well worth the cost. What say you?

At the end of the day (or at least, at the end of the planning session), any estimation is just a guess: sometimes its more, and sometimes its less. This means that the distribution of the actual time versus the estimation should be pretty much

At the end of the day (or at least, at the end of the planning session), any estimation is just a guess: sometimes its more, and sometimes its less. This means that the distribution of the actual time versus the estimation should be pretty much  The better the estimation technique is, the steeper the curve will be, i.e. the closer actual results will be to the estimation.

The better the estimation technique is, the steeper the curve will be, i.e. the closer actual results will be to the estimation.

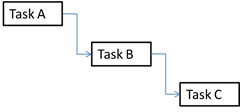

It is easy to see that the more complex a project is, the more dependencies each task has the greater the chance of being late is; The distribution of the actual duration of tasks with dependencies is a

It is easy to see that the more complex a project is, the more dependencies each task has the greater the chance of being late is; The distribution of the actual duration of tasks with dependencies is a